Much like the best player never to win a Stanley Cup (or never to win anything if you want to go further) debate, one way to get a room of hockey fans arguing for eternity is to ask who the best player to never play in the NHL is. Some people will say Soviet goalie Vladislav Tretiak, but others will suggest pre-NHL legends like Cyclone Taylor and Joe Linder, while still others will name (non-Tretiak) members of the dominant Soviet Red Army teams from the 1970s. The variety of answers will also depend on the make up of the room, as Swedish, Finish, Czech, German and even Polish, British, Slovenian and Romanian hockey fans all their own choice of player who could have made it if only given a shot.

I am not interested in arguing about who the absolute best player never to play in the NHL is as there is not really any debate. The answer is Vladislav Tretiak, full stop. However, after Tretiak, the case for a number of individual players becomes much more interesting. So rather than picking one player, lets do what we did for players who never won anything and make up an entire team. That’s right, we are going to pick 3 goalies, 6 defenders, 12 forwards who never played in the NHL.

First though, the rules. Never having played in the NHL means that they never played a regular season game in the NHL. Playing exhibition games in the pre-season or against non-NHL clubs does not ruin a player’s eligibility. Essentially, this is the Vladimir Krutov rule. The K on the KLM line with Igor Larionov and Sergei Makarov, Krutov played 61 games for the Vancouver Canucks in 1989-90 but struggled with culture shock and weight issues so returned to Europe for the 1990-91 season. While there certainly is a convincing argument that Krutov was not given an opportunity to success, he did play in the NHL so is ineligible for this team.

Additionally, I have excluded any player who played prior to the creation of the NHL in 1917. Players cannot be excluded from a league that does not exist yet. You will also notice that there are no players from before the 1930s on the team. That is a conscience choice. Prior to the introduction of the forward pass to the NHL in 1929, the game was very different, more like rugby on skates than hockey as we now know it. I am not suggesting that guys like Cyclone Taylor, Frank McGee and Joe Linder were not tremendous athletes and do not deserve recognition, rather I want to identify players who were the best at the present incarnation of ice hockey as we know it.

There were many reasons other than time that prevented the players on this team from reaching them NHL. The most obvious of these is racism, both explicitly in the case of Black players like Herb Carnegie, but also more subtly in the form of anti-European biases among NHL managers; a Don Cherry kind of racism if you like. Furthermore, politics also played a part, as Eastern Bloc Communist countries refused to let players leave to play in North America. While some did defect and a later generation of players were given permission to play in the NHL, defection plus learning a new language and living far from family and friends were serious barriers.

Pay was also a serious impediment for most of the history of the NHL. In the 1960s the average salary for a journeyman player was between $12 000 to $14 000, the same as a school principal. Especially if one had a university degree your earning potential was much greater in a profession while your chance of injury was much less. The relatively low pay also made the prospect of someone crossing the Atlantic to play that much more daunting, as the money simply wasn’t in it.

Throughout this piece I will try and highlight why each player on our team remained outside the NHL.

Goalies

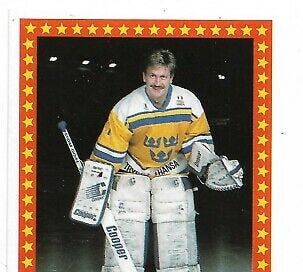

Rather than going with a starter and back up in nets, this team will have two (really three as you will see) starting goalies to split the workload. As our 1A goalie we have Swedish goalie Peter “Pekka” Lindmark. Active from 1981 until 1997 in the Swedish Elitserien, he broke into the league with Timrå IK before spending the bulk of his career with Färjestad BK and then Malmö IF where he won four Swedish titles. Internationally, he was Sweden’s starting goalie from 1981 until 1991, representing the Tre Kronar at 11 major international tournaments. During this time he won two World Championship golds (1987 and 1991), two silvers (1981 and 1986) and an Olympic bronze at the Calgary Olympics.

What is particularly impressive about Lindmark is that he was not playing on the powerhouse Swedish teams of the late 1990s and early 2000s. He did not have the luxury of lining up behind the Sedin Twins, Peter Forsberg, Daniel Alfredsson and Marcus Naslund. The most talented of all his teams was probably the 1991 team with a very young Mats Sundin and Nikolas Lidstrom, as well as established Swedish stars Hakan Loob and Mats Naslund. Of particular note is Lindmark’s performance in the 1981 and 1984 Canada Cups where he put up better numbers than NHL stars such as Mike Luit and Tony Esposito (1981) and Grant Fuhr, Tom Barrasso and Pete Peters (1984). He was also named goalie of the year in 1981 by the IIHF, beating out a guy named Tretiak who had led the USSR to their first and only Canada Cup victory that year.

I am not suggesting that I would take Lindmark over someone like Fuhr or Esposito (in his prime) but he certainly demonstrated time and time again in the 1980s that he could hold his own, and even out compete NHL stars. It did not, however earn him the interest of NHL GMs, consequently he played his entire career in Europe.

The other goalie, the 1B if you prefer, is actually two people, the Czechoslovak duo of Jiří Holeček and Vladimír Dzurilla. These two goalies formed a formidable tandem for the Czechoslovakian team in the late 1960s and 1970s when, they could claim to be one of the top three hockey playing countries in the world. The two goalies’ careers were very similar, with Holeček playing for the national team between 1964 and 1979 while Dzurilla played from 1963 to 1977. In a fitting symmetry for their country, Holeček was Czech while Dzurilla was Slovak. Both men won three golds at the World Championships (1972, 76 and 77) and an Olympic silver, although at different Olympics, with Dzurilla winning in 1968 and Holeček in 1976. Possibly even more impressive than the team honours, Holeček was named the goalie of the tournament at five World Championships, and yes, Tretiak played at those tournaments too.

Canadians are more familiar with Dzurilla due to the 1976 Canada. In the round robin game against Canada, Dzurilla outdueled Roggie Vachon to earn the Czechoslovaks a 1 to 0 victory and a place in the finals against the Canadians. A best out of three series, Canada won game one but then game two went to OT with the score tied 3 to 3 when this happened:

The goalie who is far out of his net? Dzurilla. An enduring image for a goalie who deserved much better. Given that both men played in Communist Czechoslovakia there was no chance they would be allowed to play in North America. By the time many of the stars of those 1970s teams were able to play in the NHL, Dzurilla and Holeček’s careers were over.

Defence

The first pairing on our team were stars of their respective national teams during the 1960s and 70s. Our number one defenceman is Alexander Ragulin of the Soviet Red Army. Ragulin is widely considered to be the best defender from the Soviet era. He played for the USSR national team for thirteen years where he won three Olympic golds (1964, 68 and 72) as well as an incredible ten World Championship golds plus one bronze and one silver to round out his collection. He also came within a Paul Henderson goal of winning the 72 Summit Series. Finally, in terms of individual awards he was named top defenceman by the IIHF in 1966.

Like most defenders of his day, Ragulin was a defence first player, only scoring 29 goals in 239 career international games. But like all Soviet defenders, who could skate and pass with the best players in the game, while not being afraid to play physical. Ultimately, given the era he played in it was doubtful that any NHL GM would be willing to sign a Russian player. Furthermore, given the importance that the USSR placed on sporting achievement, there was no way he would have been allowed to play in North America even if someone offered him a contract.

Joining Ragulin in our top pairing is Czech defender František Pospíšil. He spent a decade (67 to 77) patrolling the blueline for the Czechoslovakian national team and protecting either Jiří Holeček or Vladimír Dzurilla. In that time he won three World Championship golds (1972, 76 and 77), two Olympic silvers, one bronze and two Golden Stick Awards, which recognized the top Czechoslovakian player of the year. As best I can tell, he also was not on the ice for Sittler’s goal in OT in 76 despite playing in all seven games of the tournament. He also faced off against Ragulin in three finals, only once getting the better of his Soviet counterpart.

Pospíšil also nicely balances out Ragulin’s stay at home tendencies. The Czech defender put up 45 points in 97 career World Championship games and 12 points in 19 career Olympic games. In terms of international play, that makes him the highest scoring Czech defenceman in history. Unfortunately for Pospíšil, his career was over by the time many of his younger teammates like Jiri Bubla went to play in the NHL in the early 80s.

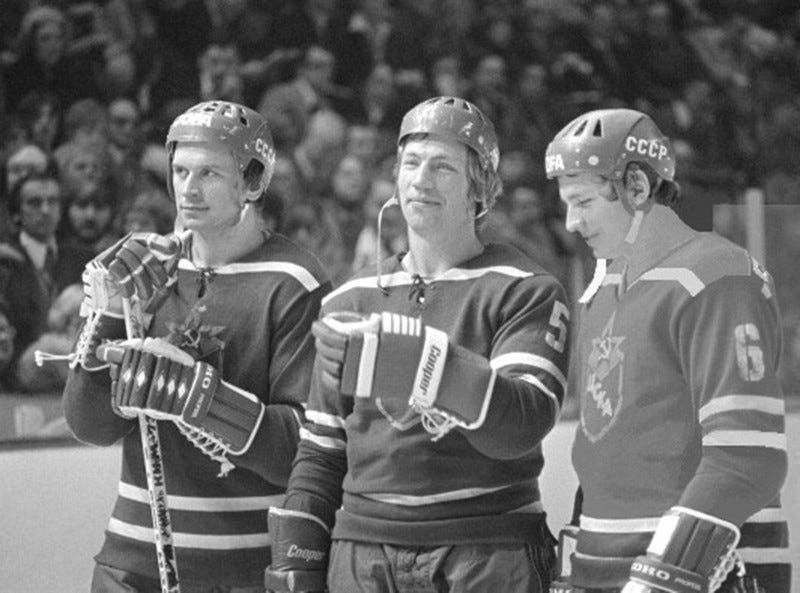

Our second pairing could well be the top pair on any team in the world during the late 1970s. The Red Army duo of Vladimir Lutchenko and Valeri Vasiliev are our third and forth defencemen. Both players were born in 1949 and debuted for the Red Army within a year of each other, Lutchenko in 1969 and Vasiliev in 1970. Both won eight World Championship golds and two Olympic golds and played in the 72 and 74 Summit Series, winning against Team Canada 74 with a 4-1-3 record. Combined with Tretiak in nets and the forward line of Valeri Kharlamov, Boris Mikhailov, and Vladimir Petrov (who we will hear more about soon) they made up one of the best units in hockey history.

The main difference between the two is that Vasiliev stuck with the Red Army team until 1982, meaning he got to play with the famed KLM line and be part of the 1981 Soviet Team that dethroned Canada at the Canada Cup.

Vasiliev is the more offensive of our pair, ranking third all time in Soviet Defender scoring totals. Also, as Gerry Cheevers found out during the 74 Summit Series, Vasiliev had a wicked slapshot from the point. While Lutchenko is forth on that same all time list, there is a big gap between the two and he never managed to score a goal at the Olympics in 11 games. Much like all Soviet defenders though, the two men could skate and pass as well as their more offensive teammates. They also could hit and play dirty when required.

While by the 1970s NHL GMS were willing to sign European players and WHA GMs were even more willing to do so, the Red Army was still unwilling to let its players go play in North America. Consequently, neither of these two dominant D-men got to play in the NHL.

Our final pairing is made up of guys whose heyday came much earlier than our top four defenders. Brit Carl Erhardt, captain of the UK’s Olympic gold medal winning team of 1936, pairs with NCAA star, Olympic gold medalist and the only American on our team, John Mayasich.

Erhardt, unlike most of his teammate on the 1936 gold medal winning team was actually born in the UK. While most players on that team were Canadians living (and studying) in Britain, Erhardt was born in Greater London and learned ice hockey while at school in Germany and Switzerland. In addition to being the oldest man ever to win Olympic gold in ice hockey at 39, he also led Britain to a bronze at the 1935 World Championship. Part of his success was due to his incredible athletic prowess, excelling not only at hockey but also tennis, alpine skiing and water-skiing, even helping to found the British Waterski Federation.

Joining Erhardt on the blueline is another Olympic gold medalist, John Mayasich. While Mayasich started his career as a forward, he ended it as a defender, which is good enough for us. He grew up in (where else?) Minnesota and stared for the University of Minnesota Golden Gophers as a centre in the early 50s, even setting the NCAA record for points in a game with eight. He also played on the USA Olympic team in 56, winning silver and then in 1960, winning Gold in front of a home crowd. Two years later he played defence on the American national team as they won bronze at the World Championships.

Unlike most players on this list, Mayasich never played hockey full-time, instead working as a broadcaster with KS95 FM in St. Paul, MN while playing semi-pro until 1971 with the Green Bay Bobcats of the USHL. Part of the reason for pursuing broadcasting was the money and job security the career offered. However, the other part was that NHL GMs in the middle 50s refused to even consider US college players. Given the importance of the NCAA in NHL player development today, such a policy seems unbelievable. Yet as Mayasich reported to Sports Illustrated in a 1995 interview, no NHL team even approached him with a try out offer. The NHL’s reluctance to consider players outside its bubble is a subject we shall sadly have to return to.

That is it for part one. Join us on Friday for part two where we have a team with lots of Russians and Czechs and even a Slovenian!

I would put the GOALIE of the 1936 Winter Olympic " Gold " Medal Great Britain Ice Hockey Team JIMMY FOSTER on this List for the following reasons. For any Goalie that has Played at least 5 Games in Olympic Ice Hockey History " Jimmy Foster " has the HIGHEST SAVE PERCENTAGE and LOWEST GOALS AGAINST AVERAGE ever along with the overall OUTSTANDING CAREER He had! Recently inducted into The ( IIHF ) Hall of Fame in Toronto, Canada.