The Forgotten 1974 Summit Series

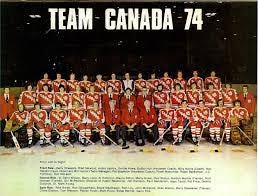

Part One: The World Hockey Association version of Team Canada

This is the first of a four part series on the 1974 Summit Series. Part One looks at the lead-up to the series and who Team Canada would face off against.

Where is Bobby Hull? The answer in 1972 was playing in Winnipeg for the Jets and that was a problem. Former Boston Bruins coach (and future GM) Harry Sinden was tasked by Hockey Canada with building and coaching the Canadian team that would face the dominant Soviet Red Army team in the 1972 Summit Series. When on July 12th he announced the initial 35 man roster he included Bobby Hull, Gerry Cheevers, Derek Sanderson (and his moustache), and J.C. Tremblay. Of these, Hull was the most controversial, as despite having led the NHL in scoring the prior season, he had just signed a $1.75 million dollars deal with the Winnipeg Jets of the upstart World Hockey Association (WHA). In order for the NHL to release its players for the series, the league demanded that all players were signed to NHL contracts by the opening of Team Canada’s training camp on August 13th.

Despite pleas from Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and, surprisingly, Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard, the NHL refused to relent. Even the resignation of Phil Reimer, a governor of Hockey Canada, made no difference. In the end, Dennis was the only Hull to play against the Soviets and Bobby, Cheevers, Sanderson and Tremblay stayed in Canada.

Of course, Henderson scored his immortal goal in Moscow and Canada won the series. But still an intriguing ‘what if’ hung over the series. How would Bobby Hull, arguably the best North American player at the time, fair against the Red Army? Well, in 1974 the world would get to see how Hull, as well as Tremblay and Cheever, would perform against the Soviets.

I am talking about the oft-forgotten 1974 Summit Series. This time around, Team Canada was composed of exclusively WHA players. Paul Henderson and Frank Mahovlich of the Toronto Toros and Pat Stapleton of the Chicago Cougars had particularly good timing as these three 72 Summit Series alumni were eligible to play in the 1974 edition, having jumped ship to the WHA after 1972.

The genesis of this series began in April of 1973. Lou Lefaive, the executive director of Sports Canada, and Gordon Juckes, a former president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association had met with Andrey Starovoytov, the General Secretary of the Soviet Ice Hockey Federation to discuss another series between the Red Army and a team of Canadian professionals. Discussions between the two countries heated up in January of 1974 when representatives of Hockey Canada met with their Soviet counterparts. Shortly afterwards, Federal Minister of Health Marc Lalonde learned about the discussions and lent the support of the federal government to the initiative. The final agreement for another Summit Series was announced simultaneously in Canada and the USSR on the morning of April 26th, 1974. The major difference was this time, the agreement was based on the principles outline by Hockey Canada President Douglas Fisher in January of 1973 that stipulated that any NHL, WHA or Canadian amateur player could be selected to wear the maple leaf.

The only problem was that while Hockey Canada and the federal government could publicly proclaim that all Canadian players should be allowed to participate, in reality they relied on the NHL to agree to release its players for the series. In 1974, the NHL was not inclined to do so. Allowing their players to play alongside WHA stars such as Hull, Gordy Howe, Frank Mahovlich, Henderson and Tremblay would be an implicit recognition by the NHL that the rival rebel league was in some sense, an equal. Furthermore, the NHL was involved in a nasty legal dispute with the WHA over the enforceability of the “reserve clause” in NHL players contracts. Finally, NHL Players Association director, the infamous Alan Eagleson, was also opposed to NHL participation in the series. All of these factors meant that the series would be an exclusively WHA affair.

The fact that the WHA would have a chance to face the Soviets was obviously fantastic news for the upstart league. Here was a chance to prove that their best could match, or even exceed, the feats of their NHL contemporaries by beating (arguably) the best hockey team in the world. However, the WHA sought to exploit their publicity advantage by insisting that they really wanted the NHL to participate. In a pre-series publicity tour, Winnipeg Jets owner Ben Hatskin and his star Bobby Hull told the Toronto press that, “We want the best team for Canada so we still hope to get NHLers. This should be above either the WHA or the NHL.” While Hull no doubt would have loved a chance to face the Red Army with NHL stars Phil Esposito, Bobby Orr, Bernie Parent and Guy Lafleur beside him, I suspect that the WHA brass like Hatskin was duplicitous to some degree in professing their desire for a combined NHL/WHA Team Canada.

However, in another part of their brains the WHA leadership must have been hoping the NHL would relent and bail out the new league. The fact was the Soviet Red Army team was one of the strongest hockey teams in the world and despite their claims otherwise, the talent level in the WHA was simply nowhere near as high as in the NHL. Unlike in 1972 when the Canadian press predicted a romp for Team Canada, the press was convinced that the Soviets would dominate the NHL-less Team Canada, much as they did at the Olympics and World Hockey Championships. John Robertson of the Montreal Star predicted that the 74 team would “lose every game by a converted touchdown” while Toronto Star reporter Jim Proudfoot stated that, “Man for man, Team Canada isn’t nearly as strong as the ’72 club.”

These fears were well founded. Seventeen of twenty four Soviet players were 72 Summit Series alumni. Since 1970, the Red Army had won gold in four of the past five World Hockey Championships as well as gold at the 1972 Sapporo Winter Olympics. Their top line of Valeri Kharmalov, Vladimir Petrov and Boris Mikhailov was one of the most dangerous trios in the world and unlike in 1972, there was no Bobby Clark to break Kharlamov’s ankle in game 6 of the series. But even more formidable was the Red Army goalie, Vladislav Tretiak.

If asked to name one member of the Soviet Red Army, I suspect that nine out of ten modern day Canadian hockey fans would say Tretiak and for good reason. He is one of the best to ever play his position and was the first non-NHLer inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1989. As an 18 year old in 1970 he became the starting goalie for the Red Army and didn’t relinquish the net for fourteen years (except when he was famously pulled in the third period against Team USA at the 1980 Olympics). As a twenty year old he started all eight games in the ’72 Summit Series and put up better numbers than NHLers Ken Dryden or Tony Esposito. By 1974 Tretiak’s dominance was firmly established. He was the reigning MVP of the Soviet league and the IIHF World Championships, had won four World Championship golds, and had a gold medal from the 72 Sapporo Olympics to boot.

It would not have been a stretch to say that the 74 incarnation of the Red Army was a better team than the 72 version. The job of selecting a team to counter this threat fell to William “Wild Bill” Hunter, the owner and sometimes coach of the Edmonton Oilers. The Saskatchewan native has been a junior hockey promoter and owner for most of his life. As the owner of the Edmonton Oil Kings in 1966 he was instrumental in establishing the Western Hockey League (WHL). In the early 70s he connected with American promoters Dennis Murphy and Gary Davidson to help expand their new hockey league called the World Hockey Association. Hunter was instrumental to the WHA. He not only was the owner and operator of the Alberta (later Edmonton) Oilers but also successfully convinced Ben Hatskin to bring the Jets to Winnipeg and put up the cash to sign Bobby Hull for his new team.

Given how integral the 74 series was to the WHA’s financial future it made sense that Hunter and Hatskin were forefront in publicity efforts. Having Hunter choose the team was not entirely a case of businessmen influencing hockey decisions. Hunter had served as the GM for the Oilers since their inception, even if the team he built was not very good. Furthermore, most of the choices were obvious and it would only be around the margins where there would be any real need for the GM to exercise any sort of judgement. The WHA had limited star power but thankfully for Hunter, all of the stars were Canadian.