This is the second of a four part series on the 1974 Summit Series. Part Two looks at the coach and players of Team Canada.

On July 31st, 1974 Wild Bill Hunter, the owner and sometimes coach of the Edmonton Oilers, hosted a colourful press conference to introduce the head coach and 25 players he had selected to face off against the Soviet Red Army in an eight game Summit Series. With the NHL refusing to release its players, all of the 74 Summit Series players and coaching staff would come from the World Hockey Association.

Toronto Toro’s head coach Bill Harris would be behind the bench. Harris was not exactly a household name and if any hockey fans knew him, it was likely as one of the dissenting voices in 1972 who predicted a Soviet win over Canada. Unlike Sinden and the 72 Team Canada leadership, Harris had observed the Soviet Red Army up close for years. After a twelve year playing career in the NHL with the Leafs, he retired to play a season on the amateur Canadian National Team, competing against the Soviets in the 1969 World Championships. After moving into coaching, he was named head coach of the Swedish Hockey Team and coached them in the 1971 World Championship where they won bronze, and the 72 Sapporo Olympics where they placed 4th. Harris had been a day one WHA coach, serving as the Ottawa Nationals bench boss. After moving (midseason no less) to Toronto and becoming the Toros, the team kept Harris on as coach. Given his experience in Europe, Harris clearly understood the scale of the challenge Canada faced.

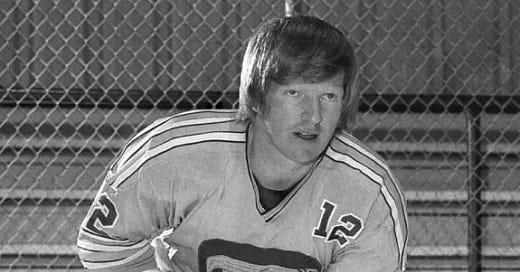

Aiding Harris behind the bench were two men who would actually be sitting on the bench. Both Bobby Hull and Pat Stapleton were named as player/coaches for the series, which was a role the two men already filled on their respective WHA teams. Having Hull on Team Canada was a major boost as he was one of the most dominant players of his age. Hull had five 50 plus goal seasons in the NHL, including his last in the league. In his first two seasons with Winnipeg Hull has scored 51 and 53 goals respectively. Despite being 35 years old Hull, was still a force and would go on to score 77 goals in the 74-75 season, a record at the time for most goals in a single season in professional hockey.

Hull’s coaching/player partner Pat Stapleton had taken longer to break into the league. Despite being only a year younger than Hull, it took until 1965 and a stop in Boston for Stapleton to earn a fulltime position on the Blackhawks’ blueline. His 50 assists during the 1968-69 was a single season record for a defenceman, even if it was broken the next by one Bobby Orr. For the start of the 1973-74 season Stapleton jumped to the WHA’s Chicago Cougars to serve as a player/coach. In his first year in the league he managed a career high 58 points and won the Dennis Murphy Trophy for best defender.

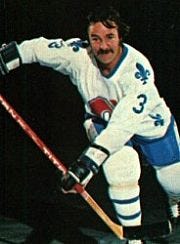

Just because Hull and Stapleton were coaches they were still going to be playing big minutes on the ice. Stapleton was the only defender among the three returnees from the 72 Summit Series and would be relied on to play big minutes. Other than their player coach, the other star on the blue line and Stapleton’s defence partner was the Quebec Nordiques’ J.C Tremblay. Tremblay had earned a full-time spot in the NHL with the Montreal Canadiens for the 1961-62 season. Never a physical player he quickly impressed with his skating and passing abilities. Originally selected for the 72 series, Tremblay was dropped after signing with Quebec in the WHA. In his first two seasons in the provincial capital Tremblay put up 142 points and earned All Star honours.

Beyond Stapleton and Tremblay, Canada’s blue line did not inspire a whole lot of confidence. It featured a teenage Marty Howe, pugilist Rick Ley and his Hartford defence partner Brad Selwood, as well as stay at home d-men Rick Smith and Paul Shmyr of the Minnesota Fighting Saints and the Cleveland Crusaders respectively. Rounding out the defence corps as extras were Al Hamilton and Barry Long from the Oilers. Especially once the series shifted to the bigger international ice surface in Moscow for games 5 to 8, Canada’s lack of mobility on the backend would be seriously exposed.

The forward corps inspired a little more confidence. In addition to Hull, hockey legend Gordie Howe would get a chance to play against the Red Army. Having retired in 1971 for a front office job with the Red Wings, Howe was not able to play in the 72 series. However, after coming out of retirement in 1973 to join the Huston Aeros and play with his two sons Mark and Marty, Howe was eligible to play in 74. Despite being well into his forties, Howe was still an offensive force, scoring 199 points in 145 games to start his WHA career. Additionally, Gordie’s eldest son Mark was still playing left wing in 1974 (he would later switch to defence) and he had proven himself a point per game player in the WHA.

Beyond Howe sr., Canada also had another NHL legend on the team in Frank “Big M” Mahovlich. A member of Team Canada in 72, he had put up big numbers with Montreal in the early 70s after stops in Toronto and Detroit, where he played with Howe. Having scored over 1100 career points in the NHL, the Big M returned to Toronto, the city his career began in, to play with fellow 72 alumni Paul Henderson on the Toronto Toros. Unlike Henderson however, Mahovlich had only scored one goal during the 72 series and was determined to make up for his poor performance two years earlier.

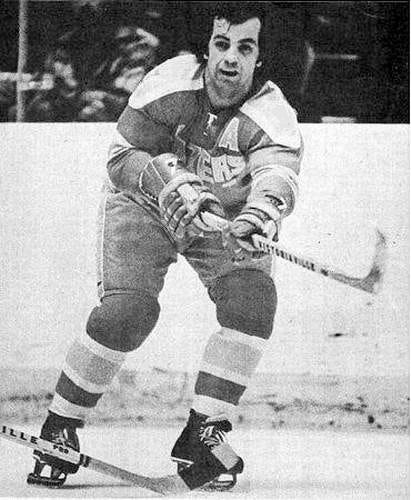

One of Canada’s top offensive weapons was not included in the list of household names and future Hall of Famers above. Rather, it was Andre Lacroix. A middling player on a strong early 1970s Philadelphia Flyers team, Lacroix followed up a weak season with the Blackhawks by returning to Philly, but this time with the WHA’s Blazers. While Derek Sanderson was the marquee signings for the new team, Lacroix became the star. He scored 50 goals and 124 points in his first (and only) season with the Blazers, good enough to lead the league.

Lacroix’s efforts were not enough to keep the Blazers in Philly and when ownership announced a move to Vancouver, Lacroix refused to go. He was traded to the New York Golden Blades (who by November were the New Jersey Knights) where he finished second in league scoring that year with an astounding 80 assists. His performances over his first two years in the WHA vaulted him from someone the 72 leadership never gave a thought to, to one of the players first selected for the 74 team.

Finally, in nets Canada had the choice between one solid starter, a minor league journeyman and one of the most colourful players ever to strap on the pads. Canada’s undisputed starting goalie was two-time Stanley Cup winner Gerry Cheevers. While he never put up astounding numbers compared with peers such as Ken Dryden and Tony Esposito, Cheevers could win games. His 32 game undefeated streak still stands as an NHL record and his clutch performances during the Boston Bruins’ 1970 and 1972 Stanley Cup winning playoff runs cemented his status as a true “money” goalie. In 1972 he switched to the WHA, signing with the Cleveland Crusaders. In his first two seasons in the WHA, he finished top two in the league in wins and goals against average. With Bernie Parent leaving the WHA after only one season, Cheevers was the obvious choice to start in nets for Canada.

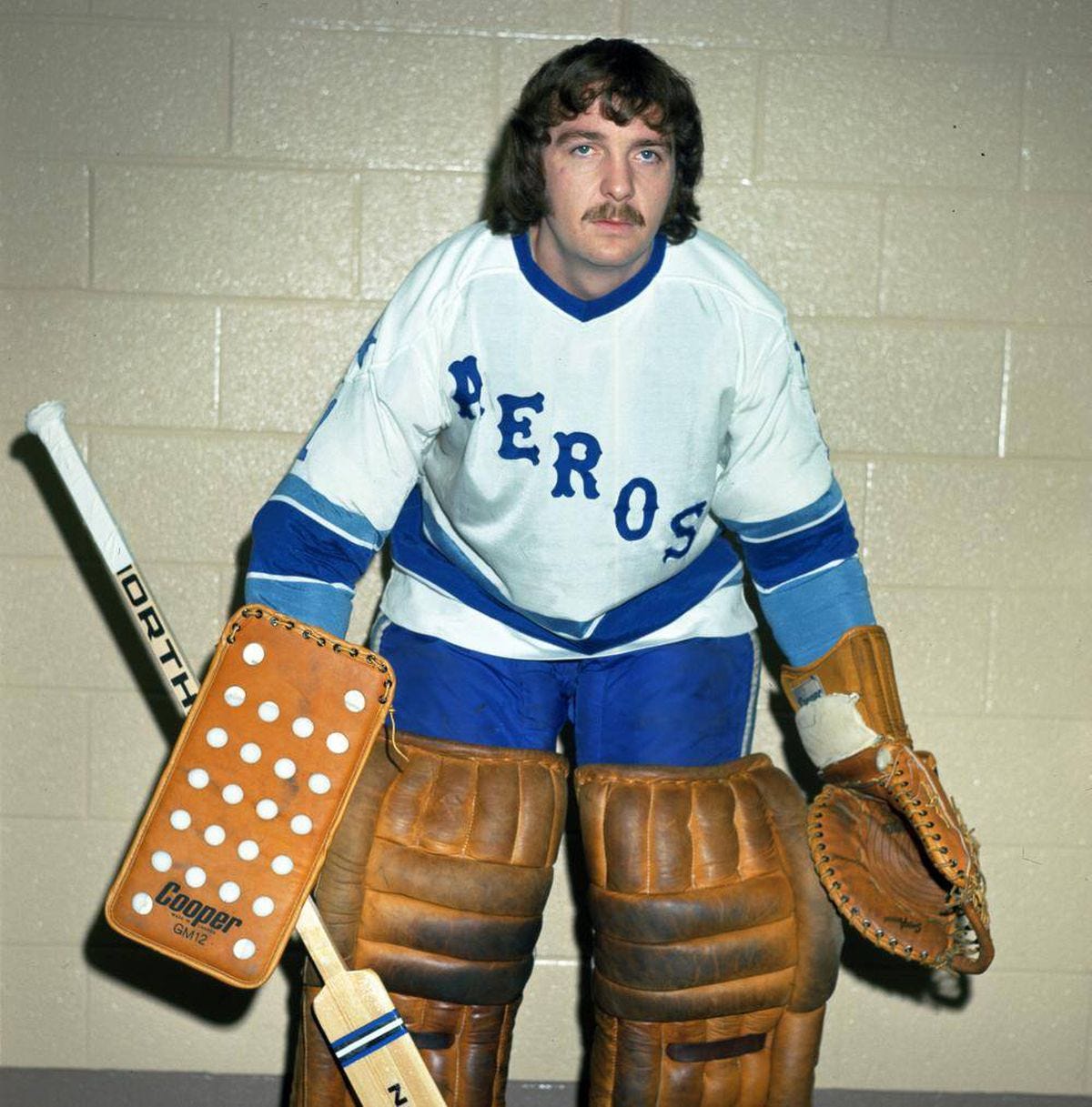

Who would be the back-up goalie was less clear. The choices were a career journeyman who had put together a break out season at the age of 26 or an exceptionally eccentric 21 year old Quebecois goaltender. The position ultimately went to the more experienced Don “Smokie” McLeod. McLeod had played junior hockey on Bill Hunter’s Edmonton Oil Kings which did not hurt his chances. He then bounced around the American Hockey League and the Central Hockey League, making a grand total of 18 NHL starts between 1970 and 72. However, in 1972 he signed with the Huston Aeros. After an undistinguished first season, he caught fire in his second season and along with the Howe family, led Huston to their first and only AVCO Cup victory. On the basis of this season, plus his connections with Howe and Hunter, McLeod was named as the back up for Team Canada.

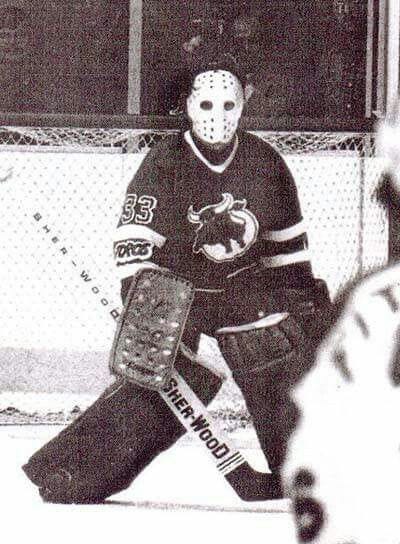

The third option in goal was a young Francophone named Gilles Gratton. Gratton was drafted by the Buffalo Sabers in 1972 but instead of joining the NHL, signed with the Ottawa Nationals of the WHA. Gratton moved with the team to Toronto when they became the Toros partway through the 72-73 season. As the youngest starting goalie in the league, Gratton showed flashes of talent, especially on a weak Ottawa Nationals team. However, his eccentricities often overshadowed his promise. Nicknamed Gratton the Looney by teammates, he was an avid believer in astrology, allegedly once refusing to play because the moon was not correctly lined up with Jupiter. He also told teammates he was a reincarnated soldier from the Spanish Inquisition and that due to stoning heretics to death in his previous life, he was fated to be a goalie. Despite a short career in the NHL, many people actually recognize Gratton due to his snarling tiger mask he wore while with the New York Rangers. When wearing this mask he would reportedly take on the persona of a cat, hissing, yowling and growling at opposing shooters. Gratton’s antics became so well known that he was reportedly the inspiration for Slapshot character Denis Lemieux, the Charleston Chiefs Quebecois goalie. Unfortunately for Canada (or fortunately for the Red Army?) Gratton only played a few minutes during game 3 of the series and no Soviet player reported any growling.

With the roster set it was time for the games to begin! Game one was scheduled for September 17th in Quebec City with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau scheduled to drop the (ceremonial) opening face off.