Why Mackenzie King and the Liberal Party Won the 1935 Federal Election

A response to Bruce Maxwell's new book Failed Promise: Five Reasons R.B. Bennett Lost the 1935 Canadian Federal Election.

As the title of this blog suggests, I spend a lot of time thinking about the 1930s. I even wrote an entire PhD thesis about Canadian politics during the 1920s and 30s. Yet it seems I am not alone. While my project only took eight years, Bruce Maxwell, an independent historian and teacher at Selwyn House School in Montreal, has spent the past twenty years researching and writing about politics in the 1930s! His new book, Failed Promises: Five Reasons Why R.B. Bennett Lost the 1935 Canadian Federal Election, is the result of this work and discusses five reasons why the Conservatives under Bennett lost to the Liberals and their leader William Lyon Mackenzie King in 1935. On May 6th, 2022, Maxwell also appeared on the Champlain Society’s podcast Witness to Yesterday to discuss his book and the 1935 election in general.

As both the book and the podcast demonstrate, Maxwell is an expert on the period and the people involved. Furthermore, I do not disagree with any of the five reasons that he lists as the causes for the Conservatives losing the election. Rather, I want to add a sixth reason to the list and argue that it is the most important of all them all. The key factor in deciding the 1935 election was voters’ concerns over the health of Canadian democracy. Essentially, I argue that the Liberals won the 1935 Federal Election because they successfully painted the Bennett-led Conservatives and the newly formed Cooperative Commonwealth Federation as threats to Canadians’ freedom and democracy.

Observant readers will realize that this post is not the first time I have talked about the 1935 Federal Election. In February, I wrote about that particular campaign in some detail, and how it represented the high water mark of Nazi and Communist fearmongering in Canadian politics. Some of the contextual information I discuss will be repetitive but my purpose this time around is different. I am not going to explicitly connect 1935 to today, or explain why I think understanding the election of that year is critical to grasping Canadian political development, although it is. Rather, I simply want to wade into the historical weeds and grapple with the specifics of that time and place.

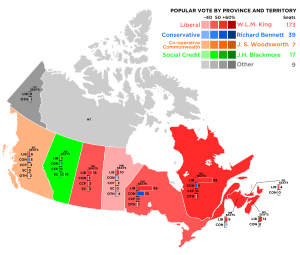

First, in order to understand the results on election night 1935 we need to examine not only the total seats won but also the popular vote totals. The most eye-catching number is obviously the swing in seats between the Conservatives and the Liberals. At dissolution, the Conservatives held 137 seats in the House of Commons compared to the Liberals 89. After all the voters had been counted, the Liberals had 173 to the Conservative’s 39. Prior to the 1993 collapse of the Conservative Party, the 1935 election marked the single largest loss of seats (98) by the Conservative Party in one single election.

The change in popular vote totals was also significant but only for one party. The Conservatives went from winning 47.8% of the vote to 29.8%. However, the Liberals popular vote totals remained static at 44%. With voter turnout remaining the same at 73%, the larger electorate (10.3 million in 1935 vs. 8.8 million in 1930) meant roughly an additional 530 000 Canadians voted. Of these new voters, the Liberals won 47%, with 251 000 choosing a Liberal candidate in their riding. So, while the Liberals increased their seat total by almost 100, they did so without shifting voters away from the Conservatives and back to the Liberals.

So where did the Conservative voters go? The short answer is to third parties. Maxwell discusses this factor in chapter 4 of his book and he is right that the proliferation of third parties hurt the Tories. Of the five parties to win seats in the Commons in 1935, only the Liberals and Conservatives had contested the previous election. Possibly most damaging for the Bennett government was the Reconstruction Party led by Vancouver native and Kootenay East MP H.H. Stevens. A cabinet minister in both of Arthur Mieghan’s short lived administrations during the 1920s, Stevens had served as Bennett’s Minister of Trade and Commerce since 1930. As minister, he spearheaded the Royal Commission on Price Spreads and Mass Buying in 1934 to investigate claims of profiteering and price fixing by Canadian businesses. However, when the commission reported in 1935, Bennett declined to act on its recommendations. In retaliation, Stevens quit the Conservatives and founded the Reconstruction Party in spring of 1935. This new party only managed to win one seat in October, that of Stevens’s in Kootny East, but they did win over 400 000 votes across the country, dealing a serious blow to Bennett’s electoral fortunes.

Also of note was the emergence of the federal wing of the Social Credit Party. Based on the unorthodox economic writings of C.H. Douglas, a British engineer, roving lecturer and anti-Semite, the Social Credit movement in Alberta garnered a substantial following during the early years of the Depression. Nominal head of the movement, Evangelical radio preacher William “Bible Bill” Aberhart, soon brought the movement into Alberta provincial politics, winning power in the province in August of 1935, only two months before the federal election of that year. Social Credit sought to capitalize on their provincial success and ran candidates federally as well, winning 15 seats in Alberta and two in Saskatchewan. This success came at the expense of the Conservatives, whose seat total in the two provinces dropped from a combined ten seats to two.

Overall, the impact of third parties on the Conservatives in 1935 reflects a broader trend in Canadian politics. As political scientists Richard Johnson has argued, when third parties prosper in Canada, the Tories lose. So why am I arguing that it was actually Mackenzie King and the Liberals who won the 1935 election when the obvious narrative is that Bennett couldn’t keep his supporters from drifting away to smaller parties? Part of the reason is the fifth and final party to win seats in the 1935 election, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the forerunner to today’s NDP.

The CCF was the oldest of the new parties to throw their hat into the ring. Yet, much like the Reconstruction Party, they were a new party led by a highly experiences MP. In this case, it was Winnipeg MP and Reverend J.S. Woodsworth, who was first elected as an Independent Labour Party member for Winnipeg Centre in 1921. In 1932, members of the Progressive Party, United Farmers Party, the Labour Party and the League for Social Reconstruction (LSR) came together in Calgary to form a new federation with the purpose of “establishing in Canada a cooperative commonwealth.” A year later in Regina, the group met and approved the Regina Manifesto, a document outlining what exactly this commonwealth would look like. Woodsworth served as the National Chairman of the organization as they initially rejected traditional party structures like leaders and party whips.

The constituent parts of the CCF such as the Progressive Party had caused the Liberals trouble in the early 1920s and were a key actor in the 1925-26 King-Byng Crisis. But by the late 1920s King and his party had effectively neutered the Progressives, a process I describe in detail in Chapter 2 of my dissertation. However, the November 1933 British Columbia provincial election results gave the Liberals serious cause for concern. While the incumbent Conservative Party of Premier Simon Fraser Tolmie was imploding due to internal discord, the Liberals under Thomas “Duff” Pattullo seemed position to stroll to an easy win. Yet, the CCF, only a little more than a year old, successfully challenged the Liberals, and at one point even looked poised to form government. Pattullo veered to the left politically to win votes and ultimately won a comfortable majority. The CCF, despite only winning seven of 44 seats, still formed the official opposition and garnered an impressive 31% of the popular vote.

So heading into the 1935 election, the Conservatives were not the only party facing a substantial challenge on their ideological flank. As Maxwell and others such as Larry Glassford have detailed, the Conservatives effectively shot themselves in the foot again and again during their time in office. Yet, they also offered, albeit belatedly, a program of substantial government intervention in the economy, including forming the Bank of Canada, the forerunner of the CBC, and the Canadian Wheat Board. While the party and their leader, who lived his entire five years in Ottawa in the luxurious Chateau Laurier, were deeply unpopular, their policy proposals were not. Similarly, the CCF, Reconstruction Party and Social Credit were all also campaigning on substantial government involvement in the economy, from detailed central planning (CCF) to simply giving everyone $25 dollars a month (Social Credit). The Liberals were the only party who did not include substantial economic action in their platform.

In fact, the Liberals had a strong record of opposing government intervention. Part of the reason they had lost the 1930 election was their unwillingness to offer financial assistance to provinces effected by the October 1929 economic crash and the subsequent Prairie Dust Bowl phenomenon of 1930. Unlike King, who in 1930 promised to simply stay the course and ensure balanced budget, Bennett had actually promised action. He pledged that a Tory government would use a punitive tariff to “blast” into foreign markets. Of course, this approach failed because Canada was an export reliant nation with a small domestic market. So when Canada raised its tariff, other countries did the same and exporters lost access to their key markets while the size of Canada’s domestic market wasn’t enough to entice foreign nations to lower their own tariff barriers. But that was after 1930. At the time, Bennett was at least telling suffering voters that his government would DO something. Plus, unlike King, he did not want to punish voters who lived in provinces that had elected Conservative provincial governments.

Five years later and not a lot had changed for King and the Liberals. They had spent much of their time in opposition opposing anything the Bennett government tried to do. Consequently, they needed an election strategy that would not alienate the majority of Canadians who wanted an interventionist government, but also one that would deal with a serious credibility problem. After all, why should Canadians trust King and the Liberals to deliver the necessary economic programs when they were the party with the best track record of resisting such measures?

It was clear that a large number of voters were going to abandon the Conservatives, though right up until the results came in, Bennett and the party believed they would remain in power. But would the Liberals maintain their vote? Even if Liberal voters found the Reconstruction and Social Credit Parties too far right, would they abandon the Liberals for the CCF, much as English voters had abandoned the Liberals for Labour a decade and a half earlier?

The answer for the Liberals was to tell Canadians that they were the party of democracy. The international and domestic political climate also helped lend credence to Liberal claims that democracy needed defending. With Benito Mussolini’s March on Rome and take–over of Italy in 1921 as well as the subsequent ascension of Adolph Hitler and the Nazi Party to power in Germany, two European powers were now firmly in the control of overtly fascist dictators. Additionally, in Britain Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists had gained a degree of notoriety, alerting Canadians to the threat of extreme right–wing parties in Great Britain.

More importantly, as historian Hugues Theoret details, Canada’s self–style “Canadian Fuhrer” Adrien Arcand and his Parti national social chrétien (PNSC) openly emulated Mosley’s tactics. While Arcand subsequently publicly distanced himself from the Nazis after 1937, his overt use of Nazi imagery, ritual and symbols sent a clear message regarding his intentions. When combined with the development in English Canada of Swastika Clubs and their attacks on Jewish Canadians, particularly in Toronto during the summer of 1933, as documented by Lita–Rose Betcherman in her book The Swastika and the Maple Leaf, fascism no longer seemed like an abstract or far away threat.

Furthermore, Bennett also was sufficiently publicly associated with Arcand to provide a veneer of truth to specific Liberal attacks on the Conservatives. Not only did he publicly praise some of Arcand’s less radical, but still anti–Semitic positions, he even arranged for an editorial by Arcand to be publicly distributed in Quebec. Furthermore, the Conservative leader in the Senate, Edouard Blondin, was an open admirer of Arcand and even wrote to Bennett encouraging cooperation between the two men. While the Conservatives never did work with the PNSC, these links provided ample fodder for the Liberals during the 1935 election.

The Liberals also reframed their opposition to many of the Bennett Government’s initiatives as driven by a firm and long-standing commitment to parliamentary democracy. Central to the Liberal’s claim was the idea that Bennett had abused his executive powers through his use of Orders in Council. Never has a more mundane procedural concepts sparked such heated rhetoric!

In order to understand their claims regarding orders in council, it is necessary to give a crash course in what they actually are. Initially, orders–in–council were literally an order from the King or Queen, or in the case of the North American colonies the governor, based on the advice they received from the Privy Council. However, by the 1930s, orders–in–council were initiated on a government minister's recommendation and after securing cabinet approval, were presented to the Crown as an order signed by all of cabinet for the governor general to approve. Unlike government legislation, which needed to be passed by Parliament, neither the House of Commons nor the Senate needed to approve orders in council. While the majority of these orders were simply Prerogative Orders, meaning they dealt with government appointments to the civil service, crown corporations and the Senate, in certain situations these orders could be used to authorize government action. In these cases, Parliament would pass a bill known as enabling legislation, directing the relevant minister to draft the appropriate order–in–council designed to ensure implementation of a particular piece of legislation.

Rather than rely on this level nuance, the Liberals set up a simple dichotomy between democratic legislation passed by parliament and autocratic action. To prove their point, King and his party pointed to two pieces of legislation, the Unemployment and Farm Relief Act 1931 and the Public Works Construction Act 1934, as examples of the Conservative government passing legislation through parliament that granted the executive supposedly unlimited autocratic power. In their 1935 campaign literature, the Liberals told voters that, “the present Prime Minister would have the fate of this country decided by the Executive authority of the government and not be reference to the elected representatives of the Canadian people.” Hence, the Liberals were not opposing these acts, which involved substantial government intervention in the Canadian economy, because they were against the principles behind them. No, of course not! Rather the Liberal’s opposition stemmed from their concern at how these pieces of legislation undermined Canadian democracy by giving Bennett too much power. Of course, anyone with a strong background in parliamentary procedure would see through the fallacy of the Liberal’s argument immediately, but it was not the experts whom they were tailoring their message to.

The Liberals also claimed that their objections to much of what Bennett termed “relief legislation” was based on a principled defence of the rights of parliament. In particular, they argued that it was parliament’s prerogative, not the Prime Minister’s, to determine how relief funds were spent. Any negation of this standard threatened Canadian democracy. In a campaign speech in 1935, King stated, “To be rid of the control of Parliament in the say of the amount of public monies to be or not to be expended, is going pretty far on the road to a complete dictatorship.” Without delving deeply into parliamentary procedure (once per piece is enough) King was right that the House of Commons had to approve all government spending and the executive could not use tools like orders in council to spend money. However, in the case of the relief acts, parliament had approved the total sum to be spent, it was then up to the government to administer this fund and distribute it based on the criteria outlined in the act. Essentially these acts functioned much as an organization like the Social Science and Humanities Research Council or Western Economic Diversification Canada do today, nothing scary and autocratic about it. But such claims allowed the Liberals to frame their opposition to relief measures as a principles stand against autocracy.

The Liberals were also a lot less subtle in much of their rhetoric. As I detailed in my other piece on the 1935 election, King and his party were also quite happy to call Bennett and the Conservatives literal fascists. They were also happy to label the CCF as Stalinists and communists. Possibly the most glaring example of this strategy come from King’s 1935 campaign speeches. In one he stated, “At the next election, you will have three choices. You can vote for the Tory autocracy, which is bad, for the CCF autocracy, which is worse or for the Liberal Party.” In another speech King told his audience, “The present government... had set up a tyrannous dictatorship” and that “[The CCF and Tories] were both dictatorships in their own way, and there was evidence in each case, [of] a desire to subordinate the individual.” If you want more, there are plenty of other examples that you can find in the original piece. The overall point is that the Liberals wanted to make sure voters knew that it wasn’t just the Conservatives who threatened democratic rights and freedoms, but any other party that was not the Liberals.

The core Liberal message was that the only way to get economic intervention and preserve Canada as a democratic state was to elect King. This idea was even reflected in the Liberal’s campaign slogan of “King or Chaos.” The reason the Liberals could be so dramatic and frankly, apocalyptical, in their messaging was that they were speaking to the already partially converted. King needed to convince his own supporters from 1930 to stay loyal to the party. That would, as we saw, be enough to win. The Conservatives were going to eat themselves. King’s goal was to convince dissatisfied Liberals to stick with the party by presenting the Liberals as the only alternative to chaos.

Hence why I argue that the Liberals won the 1935 election. The party faced a series of potentially insurmountable problems heading into the 1935 election. They had no policy ideas to address the most pressing issues of the day, faced a young and vibrant opposition in the CCF, and had a track record of opposing popular legislation. Instead of succumbing to defeat, King and his party reframed the public discourse from one regarding economic insecurity to democratic insecurity. When facing the Conservatives on this terrain, the Liberals had ample enough ammunition to scare their own supporters into remaining with the party. While I would argue this was a profoundly cynical strategy, it was also an effective one.

All of the factors that Maxwell lists in his book and discuses on the Champlain Society podcast were absolutely relevant to the 1935 federal election results. Yet, I argue they only set the stage and made what looked like an unstoppable Prime Minister in 1930 a weakened force. The Liberals still had to find a way to win the election and the way they did that was presenting themselves as champions of Canadian democracy. It certainly was not the first time they had adopted this tactic, see King’s overheated election rhetoric from the 1926 election during the King-Byng crisis for an earlier example, and it would not be the last. It certainly seems as if Trudeau Jr. has read some of King’s playbook.