On Wednesday we looked at goaltenders not named Tretiak and defenders. Today, its time to assemble the best 12 person forward corps we can out of players who never laced up in the NHL.

I struggled with the fact that I could have selected all twelve forwards from the Red Army teams of the 60s and 70s. However, that would make this article much less interesting, plus would exclude players like Tony Hand, Rudi Hiti and Sven Tumba who actually had legitimate shots to play in the NHL but turned them down.

For our first line we will return to the Red Army for the last time, but this time we are taking the entire line. The seventies version of the 1980s KLM line with Valeri Kharlamov, Boris Mikhailov, and Vladimir Petrov (so KPM line?) was the top unit for the Soviets for a decade and is our top line as well. So dominant were they that the three men sit first, second and forth overall in career scoring at the World Championships.

The biggest star of the three is Kharlamov, a diminutive left winger who, in his own words, “liked to score beautiful goals.” He was also famously targeted by Canadian players during the 72 Summit Series and the 74 Summit Series. When you see the type of goals he could score though you kind of understand why. Watch here as he makes Team Canada 74 look silly.

Makes you think that if Clarke had not broken Kharlamov’s ankle in game 6, Henderson’s heroics in game 8 might not have even mattered.

He joined the national team in 1969, the same year as Lutchenko, and by now you are familiar with all the medals that the 1970s Red Army team won. Unfortunately for Kharlamov, his career and life would end in tragedy. After being left off the 1981 Soviet Canada Cup team, allegedly because of a lack of fitness, Kharlamov and his wife were killed in a head on collision in Moscow in August 1981. Fans lined the streets of Moscow for his funeral and filed into CSKA Moscow’s arena to view his body lying at centre ice. An electrifying talent who scored at well over a point per game pace throughout his club and international career, Kharlamov is one player who would have lit up the NHL in the 70s.

Of course, Kharlamov’s line mates were also stars in their own right. On the opposite wing of the Red Army team and on our team is Boris Mikhailov. The captain of those teams, he played 14 seasons with the Soviet national team, winning all the medals and trophies that his peers did. In addition to his international accomplishments, he also scored a record 428 goals and 652 points in the Soviet domestic league. So influential was Mikhailov that he was one of the very few athletes to ever receive the Order of Lenin, the Soviet Union’s highest honour, in 1979. In 1980 he retired, choosing not to play with the USSR at the 81 Canada Cup.

Finally, at centre is Vladimir Petrov. At over six feet tall, he was the big centre with the two small and speedy wingers. While Mikhailov and Kharlamov would score, Petrov was more of a playmaker, recording more career assists than either of his wingers. He also put up more penalties than either of his smaller line mates too. Petrov also retired after the 1980 Olympics, after winning all the medals and trophies that his teammate did.

There is a reasonable case for bumping Petrov out of the faceoff dot and giving the spot to Alexander Maltsev, who served as the Soviet’s second line centre during the 70s. Of the three linemates, he is the least well known among North American hockey fans, partially due to his struggles in the 72 Summit Series:

But, in our case, Petrov gets the nod due to his chemistry with his line mates even if Maltsev outscored him. Regardless of who is at centre, any combination of these four forwards are in the conversation for not only the best players never to play in the NHL, but, the best players of their era. Unfortunately, politics meant fans only got to see them face off against Canada’s best rarely, and even then, internal feuding meant players like Bobby Hull missed the 72 series, while the NHL as a whole boycotted the 74 series.

Centering our second line is 2022 Hockey Hall of Fam inductee Herb Carnegie. Carnegie was a star and three time league MVP of the Quebec Senior League, even playing for two seasons on the Quebec Aces with future Montreal Canadiens legend Jean Beliveau. However, unlike his Quebec teammate, because Carnegie was Black he never got an opportunity to play in the NHL. In 1997 Beliveau penned the forward to Carnegie’s autobiography, writing, “It’s my belief that Herb Carnegie was excluded from the National Hockey League because of his colour. How could the NHL scouts overlook not one, but three most valuable player awards for a player on a team in a top senior league?”

Carnegie started playing professionally for the Toronto Young Rangers in the late 1930s. As early as 1938, Carnegie was noticed by Maple Leaf’s owner Conn Smythe, who reportedly stated that he would sign Carnegie tomorrow if he was white. Carnegie later moved to the Quebec Provincial League playing with Shawinigan, Sherbrooke and Quebec City. His best season came in the league came in1947-48 when he scored an astounding 127 points in 56 games. On the back of this success the New York Rangers offered him a tryout and a minor league contract. However, the salary of $2700 a year was less than he was earning in the QPHL. With a family to provide for he turned down the Rangers and stayed in Canada. Carnegie retired in 1953 at the age of 35. It would be another five years before Willie O’Ree would break the colour barrier for the NHL.

On Carnegie’s wings are two European players. On left wing is German star of the 1976 Olympics Erich Kühnhackl. While Carnegie was a diminutive centre, Kühnhackl brings the size, standing six foot five and weighing in at 213 pounds. In German his nickname is “Kleiderschrank auf Kufen” which means wardrobe on skates (a reference to his size, not fashion sense) and in Finish he is known as Iso-Eerikki or Big Erich, for the same reason.

Widely considered the best Germany hockey player ever, Kühnhackl played his entire career, minus two seasons in Switzerland, in Germany’s Eishockey-Bundesliga with EV Landshut and Kolner EC. He also represented Germany at three winter Olympics, including winning a bronze at the 1976 games, Germany’s first ice hockey medal since 1932, and only their third ever. A point per game player at the World Championships, he is also the seventh highest scorer in men’s Olympic hockey history, tied with the great Alexander Maltsev.

On the other wing is the highest scoring players in professional hockey history, Scottish sniper Tony Hand. Playing his entire career in the various incarnations of the UK’s top hockey league, Hand scored over 4000 career points. In 1986 he became the first UK player drafted into the NHL, picked 252nd overall by the Edmonton Oilers. That year he attended Edmonton Oiler’s training camp, earning a contract offer and an opportunity to play major junior hockey the Victoria Cougars of the WHL. In three games with the Cougars, he scored 8 points, however a combination of exhaustion and homesickness led him to return to Scotland with an invite for the 87 training camp in hand. The next year he attended Oiler’s camp and earned a minor league contract with the Cape Breton Oilers of the AHL. Yet he turned it down to return to the UK.

Hand professed in his autobiography that he regretted not renegotiating the offer and pushing for a senior contract. Oilers GM Glen Sather may well have agreed to discuss terms, as he was impressed with Hand’s ability. Sather later said that, “At the training camp I could see that he had a great ability to read the ice and he was the smartest player there other than Wayne Gretzky. He skated well; his intelligence on the ice stood out.” High praise from the man who built one the Oiler’s dynasty and certainly an indication that Hand could have thrived in the NHL.

Our third line centre is Swedish legend Sven Tumba. Born Sven Olof Gunnar Johansson he became known as Tumba because multiple players on his team shared his name and this Sven was from the town of Tumba. Tumba had a sixteen year career, playing for Djurgårdens IF while representing Sweden at 14 World Championships and four Olympics. During this time he won three World Championship Golds, as well as a bronze and silver at the Olympics. On the individual level, he was named the best forward of the tournament at the 1957 and 1962 World Championships as well as leading the 64 Olympics in scoring. His career total of 186 goals for Sweden is a national record that still stands.

Tumba attended the Boston Bruin’s training camp in 1957. After scoring against the Rangers in an exhibition game and impressing in his five game North American stint, he declined a $50 000 per year contract with the club, as playing professionally would make him ineligible to represent Sweden internationally. Given Tumba’s athletic talent – he was also a talented golfer, footballer and water-skier, there is little doubt he could have played and even thrived in the NHL. He was also voted as the Greatest Swedish Hockey Player of All Time in 1999, ahead of stars such as Peter Forsberg, Nicolas Lidstrom and Ulf Samuelson. Truly a remarkable choice for our third line centre.

On Tumba’s left wing is Finish scoring winger Matti “Molli” Keinonen. A star in the SM-Sarja (the amateur forerunner to the professional SM-Liiga in Finland) from 1960 until 1974, he scored at over a point per game pace for fourteen seasons, ultimately racking up 301 points in only 267 games. As an amateur he was also eligible to represent Finland internationally, which he did at two Olympics and nine World Championships. As Finland was not yet the hockey powerhouse we now know, he never won any medals. That did not prevent the IIHF Hall of Fame from inducting “Molli” in 2002.

Slotting in on the right wing is another player from the incredible Czechoslovak team of the 1970s. Vladimir Martinec or “The Fox” played in the Czechoslovakian league from 1967 to 1981 and scored an incredible 343 goals in only 539 games. His offensive production also extended to the international arena as well, where he is the 7th all-time scorer at the World Championships with 110 points. While an Olympic gold medal eluded the Czechoslovaks, Martinec, like his teammates discussed above, won bronze in 72 and silver in 76. Unlike so many of his talented peers, Martinec’s career was coming to an end by the time players like Hlinka, Nedomansky and the Stastnys were heading west to play in the NHL.

Centering the fourth line is the first Slovakian to play on the Czechoslovakian national team. Jozef Golonka was a small and skilled centre who spent a decade (1959-69) representing his country internationally. During that time he won four medals at the World Championships (two silver and two gold), while also winning a bronze and silver at the 1964 and 68 Winter Olympics respectively. He was also over a point per game player at both tournaments, one of only a select few non-USSR male athletes to score that prolifically at both tournaments. While his size would have always presented an obstacle to playing in the NHL during the 1960s, with Czechoslovakia firmly behind the Iron Curtain he would never be given that chance.

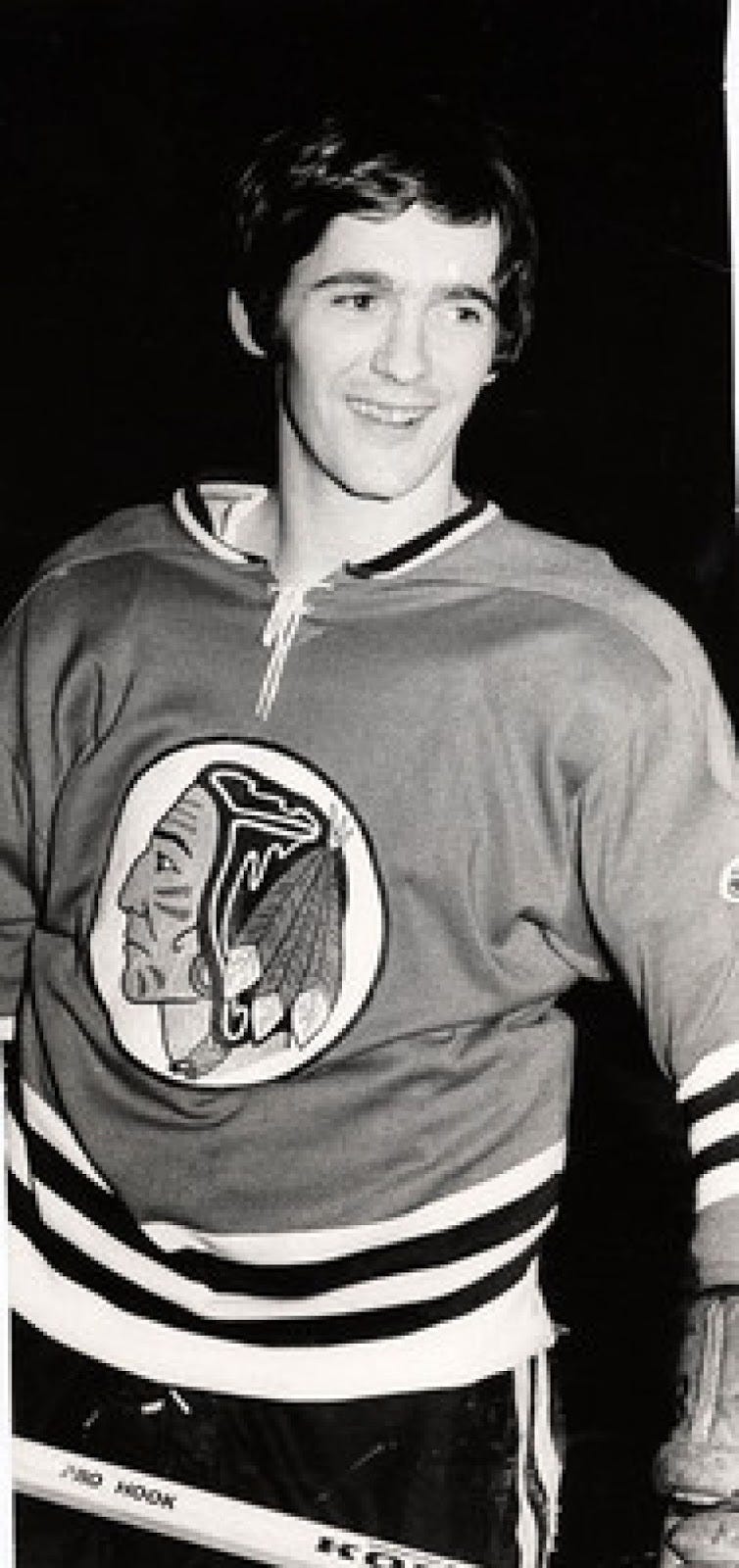

We then travel to Slovenia to find our right winger. Rudi Hiti is the best Slovenian hockey player in history not named Kopitar and was the most dominant player to ever come out of the former Yugoslavia (Anze Kopitar was 3 when Slovenia gained its independence). Hiti played in a record 17 World Hockey Championships, as well as at two Olympics, being named to the World Championship all star team four times. After growing up in Jesenice in what is now Slovenia, Hiti played his entire professional career in the Yugoslav and Italian leagues. However, in 1970 the Chicago Blackhawks saw enough in Hiti to invite him to training camp. Yet, a broken jaw on the first day of camp sent him back to Yugoslavia and ended any hope of an NHL career.

On the other wing is modern-era winger Sergei Mozyakin. Unlike many of his Soviet predecessors who had no option but to play in Russia, Mozyakin chose to play his entire career in his home country. After a very brief stint with Val-d’Or in the QMJHL in the late 90s, he joined CSKA Moscow of the (then) Russian Superleague (RSL). Although drafted 263rd overall by the Columbus Blue Jackets in 2002, Mozyakin stayed in the RSL then the KHL for his entire career. From 2005-06 until 2017-2018 he was at least a point per game player, leading the KHL in scoring in six of those seasons. Additionally, he is also the all-time regular season and playoff scoring leader in the KHL.

Internationally, Mozyakin has won six World Championship medals, including two goals. In 2018 he also captured the elusive Olympic gold, albeit as part of the Olympic Athletes from Russia (OAR) team competing under the IOC flag. While some high scoring KHL players have a difficult time transitioning to North America, Mozyakin demonstrated an ability to score at every level he played and was able to hold his own on very skilled Russian teams at the World Championships. Given that guys like Alex Radulov carved out successful careers as scoring wingers in the NHL, it is easy to imagine Mozyakin being able to settle into that role. As it is, he sits on our fourth line but will certainly be getting some powerplay time.

There we have it, three goalies, six defenders and twelve forwards. Is there someone I missed? Someone who should be cut from the team? Sound off in the comments.

I would put in the GOALIE Section of this List the Goalie of the 1936 Winter Olympic " Gold " Medal Great Britain Ice Hockey Team JIMMY FOSTER on it for the following reasons. For any Goalie that has Played at least 5 Games in Olympic Ice Hockey History JIMMY FOSTER has the HIGHEST SAVE PERCENTAGE and LOWEST GOALS AGAINST AVERAGE ever along with the overall OUTSTANDING CAREER He had! Recently inducted into The ( IIHF ) Hall of Fame in Toronto, Canada.